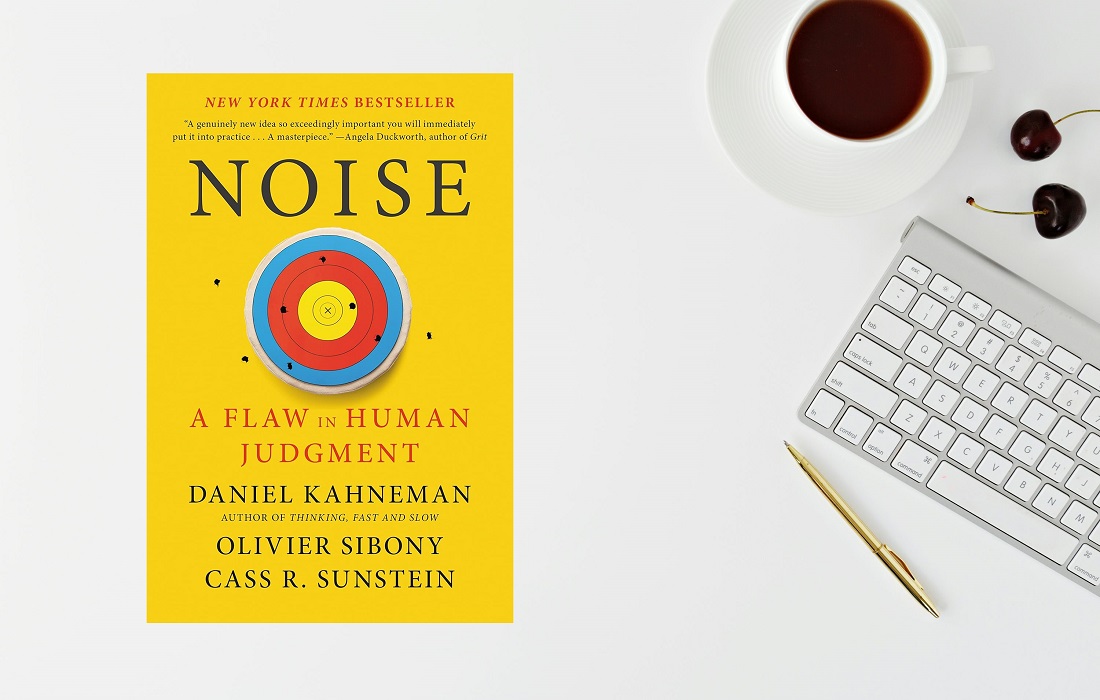

Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony and Cass R. Sunstein reveals the hidden variability corrupting decisions in law, business, medicine, and beyond. Distinct from bias, “noise” describes the random scatter in professional judgments—two experts evaluating the same case may reach vastly different conclusions. Drawing on groundbreaking research, case studies, and real-world “noise audits,” the authors expose how this often-ignored problem costs organizations billions and undermines fairness. More importantly, they present “decision hygiene” techniques to reduce unwanted variability. This book is essential reading for leaders, policymakers, and professionals aiming to make decisions fairer, more consistent, and more accurate.

+ Book Summary of Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

1. Introduction to The Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment

In the long tradition of studying human error, bias has occupied center stage. Entire literatures in psychology, economics, and law have been devoted to how systemic deviations in judgment – such as overconfidence, anchoring, and availability – predictably distort our thinking. But bias is not the only enemy of accuracy. As Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment demonstrates, there is a second, equally insidious culprit: noise – the unwanted variability in judgments that should ideally be identical.

Kahneman, Sibony, and Sunstein define noise concisely: in any situation where the same information should lead competent professionals to the same decision, noise is the degree of variation in those decisions. A criminal judge sentencing two identical cases to widely different prison terms, two doctors giving divergent diagnoses for the same patient, or two insurers quoting vastly different premiums for an identical policy all exemplify a “noisy system.”

Crucially, noise is not merely statistical “white noise” that cancels out over time. In real decision systems, each judgment applies to a different case; therefore, variations add up, creating unfairness, inefficiency, financial loss, and erosion of trust.

The book’s thesis is blunt:

Wherever there is judgment, there is noise – and more of it than you think.

While bias attracts research, media coverage, and organizational resources, noise remains overlooked, partly because it is less visible: organizations often suffer under the illusion of agreement, unaware of vast hidden divergences among their decision makers.

The authors marshal evidence from law, business, medicine, and policy to show that noise is pervasive, expensive, and curable. They advocate for noise audits, algorithmic aids, and decision hygiene practices to bring variation under control – while also recognizing that the complete elimination of noise is neither possible nor desirable.

2. Authors’ Biographies

Daniel Kahneman

– Nobel laureate in Economic Sciences (2002) for integrating insights from psychological research into economic theory.

– Pioneered the dual-system model of thinking described in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

– His work with Amos Tversky revolutionized the understanding of judgment under uncertainty and prospect theory.

+ Book Summary of Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Olivier Sibony

– Professor at HEC Paris, expert on strategy, decision-making, and behavioral strategy in organizations.

– Former McKinsey & Company partner, bringing decades of consulting experience to the study of corporate judgment errors.

Cass R. Sunstein

– Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard, renowned legal scholar specializing in constitutional law, administrative law, and behavioral economics in policy.

– Co-author of Nudge with Richard Thaler and a leading figure in applying behavioral science to law and regulation.

Together, these authors combine deep expertise in psychology, organizational behavior, and law, creating a multidisciplinary treatment of noise.

3. Purpose & Central Thesis

The book aims to elevate noise to equal footing with bias in the conversation about human error. A noisy system:

– Creates unpredictable and unfair disparities (e.g., “Refugee Roulette” in asylum cases).

– Wastes money (e.g., hundreds of millions lost in insurance underwriting errors).

– Damages trust in institutions.

Bias = Systematic deviation in a consistent direction.

Noise = Scatter – random variation – even if average judgments are correct.

Both corrupt judgment; whereas bias is visible and politically salient, noise is stealthy and requires active measurement to detect.

The authors propose three main goals:

- Define and classify noise.

- Show its real-world impact with empirical evidence.

- Offer practical methods for noise reduction without stifling necessary diversity.

4. Detailed Chapter‑by‑Chapter Summary

I will condense each part into expanded summaries while preserving core chapter ideas from your file.

Part I: Finding Noise (Chs. 1–3)

Chapter 1 – Crime and Noisy Punishment

– Originates with Judge Marvin Frankel’s critique of inconsistent sentencing.

– Before U.S. Federal Sentencing Guidelines (1987), sentencing depended largely on which judge was assigned; disparities were stark.

– Mandatory guidelines reduced variability but critics objected to mechanical rigidity.

– Supreme Court made them advisory in 2005: disparity rebounded, and personal factors (gender, political appointment) magnified differences.

– Sentencing = a case of unacceptable system noise in the justice system.

Chapter 2 – A Noisy System (Insurance Company Case Study)

– Noise audit finds 55% median difference between two underwriters quoting the same risk; 43% for claims adjusters.

– Executives had estimated only 10% variation – illustrates the illusion of agreement.

– Noise adds costs in both lost sales (overpricing) and underpricing losses – estimated hundreds of millions annually.

– Not all variability is bad; diversity of ideas in markets or creativity contexts is valuable. But in consistent-decision systems, it’s harmful.

Chapter 3 – Singular Decisions

– Distinction between recurrent decisions (repeat cases, measurable variability) and singular decisions (unique, unrepeatable).

– Even singular decisions – e.g., pandemic response – can be contaminated by analogous noise sources: differing perspectives, moods, or contextual factors between decision makers.

Part II: Your Mind Is a Measuring Instrument (Chs. 4–8)

Core Idea: Human judgment resembles a measurement tool but one that is prone to distortions from both bias and noise.

– Level noise: different average levels among judges (e.g., strict vs. lenient).

– Pattern noise: different weighting of factors by different judges.

– Occasion noise: variability in the same person’s judgment depending on timing, mood, or context.

Key Experiments:

– Mood influences leniency: e.g., Israeli court study showing parole judgments more favorable after meal breaks.

– Group decision-making doesn’t necessarily remove noise – groupthink and social pressures can amplify distortions.

Part III: Noise in Predictive Judgments (Chs. 9–12)

– Predictive judgments – e.g., insurance risk, investment returns, personnel potential – are where noise has financial cost.

– Humans make inconsistent predictions; rules & algorithms often outperform because they apply the same weights consistently (less noise).

– Obstacles to noticing noise: overconfidence, confirmation bias, reliance on intuition.

Part IV: How Noise Happens (Chs. 13–17)

Sources:

– Cognitive diversity: differences in expertise, personal experiences.

– Idiosyncratic weighting: what one judge considers crucial, another may ignore.

– Scale interpretation: two people using a 1–10 scale may mean entirely different things.

– Noise blind spots: People underestimate variability in their own group; illusion of agreement reinforced by selective exposure to dissent.

Part V: Improving Judgments (Chs. 18–25)

Decision Hygiene Principles:

- Use structured guidelines for consistent factor evaluation.

- Aggregate independent judgments to average out occasion noise.

- Delay intuitive synthesis; separate fact‑finding from conclusion formation.

- Use checklists (Appendix B).

- Employ noise audits periodically.

Case studies:

– Forensic science (fingerprints, DNA): structured protocols reduce examiner discrepancies.

– Hiring and performance ratings: structured interviews, scorecards.

– Medicine: diagnostic checklists and differential diagnosis methods.

Part VI: Optimal Noise (Chs. 26–28)

– Zero noise is neither possible nor optimal – some noise stems from legitimate value diversity.

– Trade‑offs: Cost of full noise suppression vs. return in fairness/accuracy.

– Modest algorithm integration recommended – not replacing human judgment but constraining its variability.

5. Main Ideas & Contributions

- Noise Taxonomy: Level noise, pattern noise, and occasion noise as distinct, measurable elements.

- Illusion of Agreement: Professionals can disagree vastly without noticing, due to conflict avoidance and shared but vague norms.

- Noise Audits: Empirical tool for diagnosing scatter in identical case judgments.

- Decision Hygiene: Preventive methods for systematically reducing variability.

6. Philosophical & Practical Implications

– For Business: In pricing, underwriting, hiring, performance evaluations, noise costs money and credibility.

– For Law: Sentencing disparities violate fairness principles; asylum and bail suffer “justice lotteries.”

– For Policy: Health diagnostics, immigration adjudication, regulatory approvals can be made more consistent via protocols.

– For Personal Life: Awareness of occasion noise can improve high-stakes personal decisions.

Philosophically, Noise challenges the image of human decision-making as merely flawed by bias – adding the reality that random variation is a form of injustice.

7. Reception & Legacy

Noise was praised for its clarity, depth, and applicability, though some critics saw it as overlapping with Kahneman’s earlier Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Managers and policymakers embraced noise audits and decision hygiene as actionable innovations.

8. Conclusion

The book delivers on its aim to place noise alongside bias as a core flaw in human judgment. By illuminating its hidden pervasiveness, Noise demands that institutions confront variation as seriously as they do bias. In high‑stakes domains – from justice to medicine – reducing noise is not just an efficiency measure but a matter of ethics.

Ultimately, Noise reframes human error: not only can we be wrong in the same way (bias), we can be wrong in different ways for no reason at all – and that, too, is costly.

If you found this summary helpful, please share it or leave a comment below.

7 Comments

This book was an eye-opener! I had no idea how much variability or noise could exist in decisions we assume are objective. Makes me think twice about how workplace evaluations, legal sentences, or even medical diagnoses are given.

While the idea of noise in judgments is compelling, I wonder if the book spends too much time restating examples. Still, Kahneman’s approach to dissecting decision-making bias is thought-provoking and a solid sequel of sorts to Thinking, Fast and Slow.

As someone involved in hiring decisions, I found the section on structured interviews versus free-form conversations extremely relevant. Small procedural changes can dramatically reduce inconsistency in judgments. I’m already rethinking how my team conducts evaluations and performance reviews.

The authors do an excellent job combining research with real-life examples. Particularly intriguing is the discussion on decision hygiene as a systematic approach to improve accuracy. This is a valuable contribution to behavioral science literature and public policy debates.

I don’t usually pick up non-fiction on psychology, but this was surprisingly accessible. The anecdotes about judges, doctors, and even insurance adjusters made the theoretical parts easier to follow. Now I notice noise in my own everyday decisions.

Interesting ideas, but I’m cautious. While recognizing variation in judgment is important, I felt the proposed fixes might be hard to implement in real-world messy contexts. Systems are built on humans, and humans are inherently noisy — maybe that’s unavoidable.

Daniel Kahneman’s Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment reveals how variability in human decision-making—beyond bias—leads to costly errors. Through research and examples, it shows how noise undermines fairness, accuracy, and consistency, and offers strategies for judgment hygiene to reduce it. An essential read for improving decisions in law, medicine, and business.