Few authors have captured the turbulence of the human soul like Fyodor Dostoevsky. His works blend gripping storytelling with profound explorations of morality, faith, guilt, redemption, and the forces that shape human behavior. Below is a curated look at his Top 10 Books by Fyodor Dostoevsky that changed the face of literature and continue to challenge readers today.

Top 10 Books by Fyodor Dostoevsky

1. Poor Folk (1846)

Dostoevsky’s debut novel, Poor Folk, is written in an epistolary form-letters exchanged between Makar Devushkin, a humble clerk, and Varvara Dobroselova, a young woman barely surviving in St. Petersburg. Through these letters, Dostoevsky examines poverty not as an abstract social condition but as a deeply personal, soul‑wearing experience. Devushkin’s tender but awkward affection for Varvara is overshadowed by his inability to improve her situation-and his own. The novel’s emotional weight comes from the juxtaposition of intimate feelings with the crushing realities of class and deprivation. Even in this early work, Dostoevsky’s intuition for the psychology of the oppressed shines brightly. Though less philosophically complex than his later masterpieces, Poor Folk established him as a writer of social conscience, and its raw emotional honesty makes it an enduring introduction to his work. Readers encounter the seeds of themes-dignity, compassion, the moral cost of survival-that would define Dostoevsky’s literary legacy.

2. The Double (1846)

A novella that anticipates the psychological complexity of Crime and Punishment, The Double tells the story of Yakov Petrovich Golyadkin, a low‑ranking government clerk who starts to lose his grip on reality when a man identical to him-his “double”-appears and begins to usurp his life. The work dives deep into paranoia, identity crisis, and alienation, rendered with dark humor and surreal touches. Golyadkin’s descent into madness is both tragic and absurd, highlighting Dostoevsky’s fascination with fractured selves long before Freud formalized psychoanalysis. The novella’s portrayal of mental instability remains relevant, exploring how societal pressures, personal insecurity, and bureaucratic indifference can warp a person’s sense of self. Though brief, The Double foreshadows Dostoevsky’s mature style-blending satire and psychological thriller-and mirrors the oppressive atmosphere of mid‑19th century Russian official life. It’s a compact but potent examination of self‑alienation.

3. Notes from Underground (1864)

Often hailed as the first existential novel, Notes from Underground is divided into two parts: a philosophical monologue and a personal narrative. The unnamed “Underground Man,” a retired civil servant, rails against the rationalist and utopian ideals of his time, insisting on the chaotic, contradictory nature of human beings. His reflections are sardonic, bitter, and often painfully self‑aware. In the second half, we see this philosophy in action as he recounts petty acts of cruelty, self‑sabotage, and failed attempts at connection, especially with a young prostitute named Liza. The novella captures the raw, uncomfortable truth that not all suffering has noble causes-sometimes it stems from pride and inertia. Dostoevsky probes the darker side of free will: the tendency to act against our own best interests simply to assert autonomy. This compact work is a perfect entry point for readers interested in his philosophical depth without committing to a massive novel.

4. Crime and Punishment (1866)

Perhaps Dostoevsky’s most famous novel, Crime and Punishment follows Rodion Raskolnikov, a destitute ex‑student in St. Petersburg, who rationalizes murdering a pawnbroker as a moral experiment-believing that extraordinary individuals have the right to transgress. What unfolds is not merely a crime story but an intense psychological cat‑and‑mouse between Raskolnikov, his conscience, and the relentless detective Porfiry Petrovich. The novel examines morality, guilt, justice, and redemption through vivid, tense scenes and haunting inner monologues. Raskolnikov’s slowly unraveling psyche reveals that punishment comes not only from the law but from the crushing weight of conscience. Interwoven with this are rich subplots-moral courage in Sonia Marmeladov, degradation in the Marmeladov family, and social critique of urban poverty. It’s an unflinching examination of how ideas can drive human action, for better or worse, and why redemption often requires profound humility. This book remains a towering achievement in psychological fiction.

5. The Gambler (1867)

Written under intense financial pressure, The Gambler draws directly from Dostoevsky’s own experiences with compulsive gambling. The novella centers on Alexei Ivanovich, a tutor working for an eccentric Russian general’s family in a fictional German resort town. Obsessed with the thrill of roulette and infatuated with the general’s stepdaughter, Polina, Alexei becomes trapped in cycles of hope, desperation, and self‑destruction. The narrative captures both the intoxicating allure of risk and the corrosive desperation of addiction. Dostoevsky masterfully conveys the feverish highs and crushing lows at the gambling table, while exploring questions of chance, fate, and personal responsibility. What makes The Gambler particularly compelling is its brisk pacing and the authenticity of its psychological portrait-a lucid yet empathetic view of the compulsion that nearly ruined Dostoevsky himself. It remains a cautionary tale with timeless relevance, appealing to readers drawn to high‑stakes drama and the complexities of human weakness.

6. The Idiot (1869)

Prince Lev Myshkin, the protagonist of The Idiot, is a rare figure in literature: a man almost entirely good, gentle, and devoid of guile. Returning to Russia after treatment for epilepsy in Switzerland, Myshkin enters the tangled social web of St. Petersburg, where his sincerity is often mistaken for foolishness. He becomes ensnared in a tragic love triangle involving the enchanting but self‑destructive Nastasya Filippovna and the practical Aglaya Yepanchin. The novel contrasts innocence with corruption, compassion with cynicism, and asks whether true goodness can survive in a flawed society. Myshkin’s openhearted nature exposes both the beauty and the cruelty of those around him, leading to devastating consequences. Dostoevsky imbues the narrative with social commentary, moral dilemmas, and piercing character studies. While sprawling in scope, the emotional core is intimate: a portrait of a man who tries to live by Christian ideals but is crushed by the harshness of the world.

7. Demons (The Devils / The Possessed) (1872)

Based partly on a real political murder in Russia, Demons is Dostoevsky’s scathing critique of radical ideologies. The novel portrays a provincial town overtaken by a nihilistic group whose conspiracies spiral into violence. Central figures like the manipulative Pyotr Verkhovensky and the tortured Stavrogin represent different facets of moral decay and ideological extremism. Through a cast of vividly drawn characters, Dostoevsky explores how abstract theories-when untethered from moral responsibility-can lead to chaos and destruction. The narrative blends political satire with psychological depth, offering both a prophetic warning and an engrossing tragic drama. Though steeped in the political ferment of 19th‑century Russia, its themes resonate in any age where fanaticism threatens human connection. Demons remains one of Dostoevsky’s most intense and challenging works, rewarding patient readers with insights into both political and personal corruption.

8. A Raw Youth (The Adolescent) (1875)

In A Raw Youth, Dostoevsky turns his lens on generational conflict and personal identity. The narrator, Arkady Dolgoruky, is a 19‑year‑old illegitimate son of a wealthy landowner, caught between dreams of greatness and the flawed guidance of older, morally compromised figures. Arkady’s aspirations, romantic entanglements, and business schemes unfold against a backdrop of social upheaval and family dysfunction. The novel captures the restlessness, naivety, and self‑importance of youth, while exposing the vulnerable longing for purpose and belonging beneath it all. Though less celebrated than his major works, A Raw Youth offers intricate psychological insights and dynamic character interactions, making it a fascinating study of ambition and disillusionment.

9. The Brothers Karamazov (1880)

Dostoevsky’s final novel, The Brothers Karamazov, is a sprawling epic of faith, doubt, morality, and free will. The plot revolves around the murder of the debauched patriarch Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, with suspicion falling on his three very different sons: the passionate Dmitri, the intellectual Ivan, and the devout Alyosha. Woven through the central mystery are profound philosophical debates-about God, justice, love, and the nature of evil-embodied in unforgettable scenes like “The Grand Inquisitor.” The novel’s moral complexity is matched by its rich emotional depth, exploring how ideals and desires clash within families and individuals. Often regarded as Dostoevsky’s masterpiece, it’s both a compelling courtroom drama and a spiritual meditation, leaving readers to wrestle with its questions long after the final page.

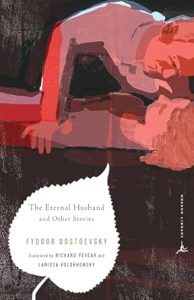

10. The Eternal Husband (1870)

One of Dostoevsky’s shorter yet haunting works, The Eternal Husband follows Velchaninov, a bachelor who encounters Trusotsky, the widower of a woman Velchaninov once loved-and possibly fathered a child with. Trusotsky alternates between hostility and pitiable dependence, creating a tense, unpredictable dynamic. The novella blends psychological suspense with dark comedy, delving into jealousy, guilt, and the strange bonds forged by shared loss and betrayal. Dostoevsky keeps the narrative tightly wound, exploring how people can be both tormentors and companions in grief. Its compact length makes it a potent and accessible entry into his psychological fiction.

Engage with Us: What Are Your Favorite Books?