In Guns, Germs, and Steel, Jared Diamond explores the roots of global inequality by asking: Why did some societies dominate others? Rejecting racial or cultural superiority, Diamond argues that geography and environment—not innate human differences—shaped history. Access to domesticable plants and animals, favorable climates, and continental axes gave Eurasia a head start in developing agriculture, technology, and immunity to deadly germs. These advantages cascaded into military power (guns), disease resistance (germs), and economic strength (steel). A Pulitzer-winning masterpiece, this book reframes civilization’s trajectory through ecology and chance, offering profound insights into humanity’s past—and future.

1. Introduction to Guns, Germs, and Steel

Jared Diamond’s “Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies” stands as one of the most influential works of popular science and history in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. First published in 1997, the book addresses one of humanity’s oldest and most provocative questions: Why did some civilizations develop complex technologies and political institutions, while others remained for millennia as hunter-gatherers or in small-scale societies? Rather than focusing on racial or cultural differences, as many scholars in the past mistakenly have, Diamond searches for the ultimate causes of these patterns in environmental and geographic factors. His thesis carried broad implications, not only for understanding the past but for re-examining how societies ought to approach issues of development, inequality, and even the future of global power structures.

Diamond’s approach is inherently multidisciplinary, blending biology, archaeology, linguistics, anthropology, geography, and even epidemiology. By tracing the earliest roots of human civilization back to the end of the last Ice Age, the book peels “the onion” of history, as Diamond describes it, and methodically builds a framework that rejects biological determinism in favor of ecological and geographic explanation. The title—”Guns, Germs, and Steel”—emphasizes the proximate agents by which Eurasian societies achieved dominance, but the substance of the book is devoted to uncovering the remote forces that led to the distribution of power, wealth, and innovation.

In this abstract, we explore Diamond’s background and motivations, the book’s intellectual structure and chapter-by-chapter progression, and its key arguments, evidence, implications, and reception. Drawing on both the book’s text and relevant scholarship, this account aims to provide a comprehensive, scholarly, and accessible distillation.

2. Author Biography and Perspective

Jared Mason Diamond, born in 1937, is a polymath whose academic career began in physiology and evolutionary biology. A professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, Diamond established himself as an expert ornithologist and field biologist, particularly in New Guinea and the South Pacific. His experiences in these areas, interacting directly with both unique wildlife and diverse indigenous cultures, led him to grapple with the question that would eventually become the foundation of Guns, Germs, and Steel.

Diamond’s moment of inspiration, as he recounts in the book’s prologue, came from a candid question posed to him by Yali, a local politician in Papua New Guinea. Yali wanted to know: “Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little cargo of our own?” Here, “cargo” referred broadly to material goods, technologies, and power. This question, more than academic curiosity, animated Diamond’s lifelong journey, and provoked him to confront common, lazy explanations grounded in supposed inherent differences in people’s intelligence or drive.

By refusing to accept racist or culture-blaming explanations, and insisting instead on rigorous scientific inquiry, Diamond positions himself as both a storyteller and a scientist. He synthesizes data, field experience, and theoretical work to demonstrate that history, ultimately, was determined by environment rather than essence, opportunities rather than internal worthiness.

Diamond’s prior academic work, notably “The Third Chimpanzee” and later “Collapse,” further solidified his reputation as an interdisciplinary thinker, but it is Guns, Germs, and Steel that remains his magnum opus. For this work, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1998, and the book has since been translated into dozens of languages, sparking debate and dialogue across disciplines.

3. Book Structure and Chapter Outline

Guns, Germs, and Steel is structured into four main parts, each focusing on a distinct phase of human societal evolution, and further subdivided into themed chapters. The book opens with the Prologue, in which Diamond sets the stage with Yali’s question and discusses the persistent inequalities of power and technology across continents. He rejects race-based explanations, introducing the notion that to understand Eurasian dominance, one must not look at human differences, but at differences in geography, flora, and fauna.

Part One, “From Eden to Cajamarca,” examines the early distribution of people, plants, and animals across continents. It explores the baseline from which different human populations began after the Ice Age and the emergence of farming and sedentary society.

Part Two, “The Rise and Spread of Food Production,” analyzes why some societies developed agriculture early while others did not, and how this gave rise to surpluses, population density, labor specialization, and technological innovation.

Part Three, “From Food to Guns, Germs, and Steel,” traces the conversion of agricultural surpluses into hierarchies, writing, centralized governments, diseases, and weapons, culminating in the ability of some societies to conquer others.

Part Four, “Around the World in Five Chapters,” is more comparative, examining the historical trajectories of major world regions, including the fates of Australia, China, Polynesia, Africa, and the Americas.

The book closes with an Epilogue that reflects on the purpose and importance of understanding world history as a science, not as a collection of stories but as a search for general principles.

Prologue: Yali’s Question and the Framework of Historical Inquiry

Diamond’s retelling of his conversation with Yali establishes the book’s core inquiry: what ultimately determined the uneven distribution of “cargo”—wealth, power, and technology? Diamond immediately identifies misconceptions stemming from racial or ethnic superiority and argues for a deeper search—one that looks beyond proximate causes, such as the presence of writing or steel, to ultimate causes like the orientation of continental axes or the availability of domesticable plants.

He sketches the broad landscape of pre-colonial history: Eurasian societies built empires and industrial machines; the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, and Polynesia manifested different paths. He emphasizes that as of 11,000 BCE, all humans on all continents were hunter-gatherers. Everything that followed, from metallurgy to the Industrial Revolution, built upon tiny differences that gradually concatenated into massive disparities.

4. Core Thesis and Theoretical Framework

Diamond’s argument, often described as “geographic determinism,” is that environmental differences—specifically, the plants, animals, and axes of landmasses—explains the uneven development of complex societies. The title refers to the proximate agents by which Eurasian societies established dominance: guns, germs, and steel. However, the bulk of the book investigates the deep foundations:

1. The earliest societies to develop agriculture, animal domestication, and sedentary lifestyles gained a head start in social and technological progress, enabling further innovations.

2. Differences between continents—their shapes, ecological diversity, and connections—influenced how easily plants, animals, people, and technologies could spread.

3. These differences (in plants, animals, and continental geography) explain why the Fertile Crescent, China, India, and Europe surged ahead, while places like the Americas, Australia, and sub-Saharan Africa lagged behind, not because of inherent differences among peoples, but because of their available resources and constraints.

Diamond explicitly calls attention to the distinction between proximate and ultimate explanations. “Why did Europeans conquer the Americas?” The proximate answer is because of their guns, germs, and steel. The ultimate explanation is rooted in the environmental prerequisites for acquiring these advantages.

PART ONE: From Eden to Cajamarca

This section explores how and why human societies evolved differently in prehistory.

Chapter 1, “Up to the Starting Line”, describes how, as of 11,000 BCE, human populations existed on all major inhabitable continents, all as hunter-gatherers. He explores the Great Leap Forward—what anthropologists call the surge in technological, social, and artistic complexity in Homo sapiens roughly 50,000 years ago, distinguishing us from Neanderthals and other hominids. The subsequent human migrations took people from Africa to Eurasia, Australia, and eventually the Americas.

Diamond then dissects the impact of initial conditions: The starting positions of different human populations—beginning with the distribution of species, available raw materials, and geography—shaped their developmental paths. He traces the peopling of the continents, the development of early tools, and the role of environmental constraints.

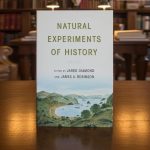

Chapter 2, “A Natural Experiment of History”, offers Polynesian island societies as a natural laboratory for comparing the effects of environment on human society. On islands with limited resources, societies remained small and relatively egalitarian; on islands with lush environments and abundant food, societies developed political centralization, intensive agriculture, and even early forms of warfare. These ecological experiments throughout the Pacific show that environment, not innate disposition, determined whether societies became kingdoms or stayed as tribes.

Chapter 3, “Collision at Cajamarca”, uses the meeting of Francisco Pizarro and the Inca emperor Atahuallpa in 1532 as a microcosm of the book’s main question. Pizarro’s small band of Spanish conquistadors, using steel swords, firearms, and riding horses, overwhelmed a much larger Inca force. European diseases, unintentionally carried from across the Atlantic, would soon devastate indigenous populations. The encounter at Cajamarca explains how the proximate factors—technological superiority and epidemic disease—are themselves products of geography and the thousands of years of development since the Neolithic Revolution.

PART TWO: The Rise and Spread of Food Production

Chapters 4 to 10 form the analytical heart of the book, addressing the development and diffusion of agriculture, animal husbandry, and their consequences.

Chapter 4, “Farmer Power”, asserts that societies which moved from foraging to food production gained the capacity for food surpluses, supporting larger populations, social stratification, occupational specialization, and advanced technology. These changes depended on local availability of suitable plants and animals to domesticate.

Diamond rigorously catalogues the world’s domesticable plants (such as wheat, barley, rice, maize) and food animals (e.g., sheep, goats, cows, pigs, horses), finding that almost all originated in certain locations—most notably the Fertile Crescent, but also parts of China, Mesoamerica, and the Andes.

Chapter 5, “History’s Haves and Have Nots”, explores why some regions (the Fertile Crescent, China, Europe) birthed agriculture and others did not. The answer lies in the local diversity of species and the presence of potentially domesticable plants. For example, Eurasia boasted a larger number of suitable endemic plants than Africa, Australia, or the Americas.

He investigates the process by which food production developed—not as an abrupt revolution, but often as a gradual shift, with societies sometimes returning to foraging during difficult years. As plants and animals were domesticated, their spread was facilitated or hindered by the orientation of continents: Eurasia lies along an east-west axis, promoting rapid dissemination of crops and livestock across similar latitudes, climates, and day lengths. By contrast, the north-south orientation of Africa and the Americas presented ecological barriers, slowing or halting the spread of innovations.

Chapters 6–7 examine what enabled some plants and animals to be domesticated but not others, and why ancient domesticators had better luck in some places. Key points include:

– “The Anna Karenina Principle” (from Tolstoy): All domesticated animals share a set of favorable traits, and any species lacking just one will be impossible to domesticate. Of thousands of large mammal species, only about a dozen have been widely domesticated for production.

– Many wild plants and animals could not be tamed or cultivated due to deficiencies such as aggressive temperament, slow growth, refusal to breed in captivity, or unsuitable diet.

Chapter 8, “Apples or Indians”, asks why some ecologically promising areas, like the eastern United States, never domesticated local plants but instead adopted imported crops.

Chapter 9, “Zebras, Unhappy Marriages, and the Anna Karenina Principle”, explains why Africa’s zebras, despite looking like horses, resist domestication—aggressiveness, panicked flight response, and other traits make them unsuitable. Eurasia, uniquely, housed animals like horses, cattle, sheep, and goats whose biology and temperament favored domestication.

Chapter 10, “Spacious Skies and Tilted Axes”, expands on the consequences of east–west versus north–south continental axes. Eurasia’s broad, unbroken east–west expanse enabled the swift spread of agriculture, livestock, and technology, while the Americas and Africa’s north–south orientation created formidable climate barriers.

PART THREE: From Food to Guns, Germs, and Steel

Diamond details how agricultural surpluses enabled higher population densities and more complex societies—the crucible for invention and conquest.

Chapter 11, “Lethal Gift of Livestock”, tackles the role of infectious diseases in history. Diamond describes the process by which epidemic diseases like smallpox, influenza, and measles emerged from close contact with domesticated animals, then evolved into devastating human plagues. Eurasian societies, exposed for thousands of years, built immunities; when Europeans arrived in the Americas, they unwittingly carried deadly agents against which indigenous peoples had no defense. This “lethal gift” was as instrumental in conquest as any weapon.

Chapter 12, “Blueprints and Borrowed Letters”, is concerned with the invention of writing and record-keeping. Societies that developed writing could expand, administer complex operations, communicate orders and history, and build institutions. Again, writing systems arose independently only a handful of times in human history, notably in Sumer (Mesopotamia), Mesoamerica, China, and Egypt. Elsewhere, systems were borrowed or adapted from neighbors; the spread and development of writing, too, depended on head starts and geography.

Chapter 13, “Necessity’s Mother”, examines technological innovation, refuting the myth of “heroic invention” by lone geniuses. Diamond asserts that the relative rate of invention is largely a function of societal size, interconnectedness, and the accumulation of previous advances. Larger populations and greater exchanges of goods and ideas, he argues, increase the likelihood of innovation—thus reinforcing the Eurasian advantage.

Chapter 14, “From Egalitarianism to Kleptocracy”, explores the emergence of centralized government, bureaucracy, and religious institutions. Agricultural surpluses allowed some individuals to specialize as warriors, priests, or bureaucrats, and to create hierarchical societies. Government and religion became tools for organizing, mobilizing, and, at times, oppressing large populations.

PART FOUR: Around the World in Five Chapters

Here, Diamond compares case studies from around the world, each providing further support for his main arguments.

Chapter 15, “Yali’s People”, contrasts the histories of Australia and New Guinea. Despite their proximity, the two regions evolved very differently due to differences in geography and biology. Australia, with poor soils and little potential for food production, remained largely hunter-gatherers, while New Guinea’s more favorable environment led to intensive agriculture but not to complex states—due partly to isolation and a lack of domesticated animals.

Chapter 16, “How China Became Chinese”, presents the history of East Asia’s empires and the unification of China, highlighting the role of geography, crop distribution, and political centralization.

Chapter 17, “Speedboat to Polynesia”, traces the history of the Austronesian expansion, the remarkable peopling of the Pacific islands by seafaring peoples, and the resultant diversity of societies shaped by island environments.

Chapter 18, “Hemispheres Colliding”, analyzes the fateful moment when Eurasia and the Americas came into direct contact, symbolized most dramatically by the conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires. Crucial here is the previously accumulated reservoir of Eurasian advances—writing, metallurgy, domesticated animals, and epidemic diseases—that proved decisive in these encounters.

Chapter 19, “How Africa Became Black”, presents a synthetic account of Africa’s unique trajectory, complicated by climatic variation, the orientation of its landmass, and the conflicting rhythms of technology and population movement.

Epilogue: The Future of Human History as a Science

Diamond concludes by considering the potential and limitations of using scientific reasoning to understand history. He hopes for a future in which historians and scientists collaborate to discern law-like generalizations about humanity’s past, rejecting both racism and simplistic “great man” narratives.

He adds that understanding the root causes of societal differences can help inform current global policies, combat stereotypes, and inspire solutions for contemporary problems of inequality and development.

5. Key Themes and Takeaways

Environmental Determinism and Geographic Luck

The unifying insight of Guns, Germs, and Steel is that success and failure of societies have little to do with the intrinsic abilities or failings of their peoples, and almost everything to do with “geographic luck”—the hand that environment deals in terms of domesticable plants and animals, landscape connectivity, and exposure to other societies.

Diamond’s analysis is careful to avoid determinism that negates human agency, but he demonstrates incontrovertibly that critical thresholds in societal complexity could only be crossed where natural endowments permitted surpluses, density, and specialization. This argument directly rebuts old, racist theories of history, providing a materialist and ecological explanation that is both humane and thoroughly documented.

The Domino Effect of Early Agriculture

The book’s close examination of agriculture and its consequences sits at the heart of its explanatory power. Where food production began, societies could support non-farming elites, write, invent, organize, and expand in ways impossible for smaller hunter-gatherer bands. Food production created armies, classes, governments, and technology, and determined which societies built up the lethal package of “guns, germs, and steel.”

The Power—and Vulnerability—of Pathogens

Perhaps the most chilling lesson of Diamond’s book is the importance of epidemic disease in history. Diseases like smallpox, which originated in the microbial milieus of dense Eurasian cities, devastated populations in the Americas and other isolated regions. Germs were accidental weapons more deadly than swords or guns, underscoring the tragic contingency of history.

Technologies and Institutions as Accumulative and Communal

Diamond’s treatment of invention and innovation undermines the “heroic individual” view of history. Inventions occurred where populations were large and societies interconnected, and they spread more quickly where the geography promoted contact. No civilization developed in a vacuum; exposure to ideas mattered just as much as individual ingenuity.

The Axes of Continents

A key technical point is the layout of the continents: Eurasia’s east–west axis allowed wheat and cattle to move thousands of miles from the Fertile Crescent to China, while the Americas’ and Africa’s north–south axes presented ecological barriers, restricting the transfer of crops and animals, and so stalling social evolution at local maxima.

6. Critiques and Alternate Perspectives

Although “Guns, Germs, and Steel” has won wide acclaim, it is not without criticisms. Some historians and social scientists charge that Diamond’s environmental determinism gives too little weight to cultural innovation, contingency, and the agency of particular leaders. Others note that he places less focus on the role of institutions and patterns of governance. Some view his approach as flattening the unique stories of peoples and regions into over-generalized laws.

Nevertheless, the book’s core findings remain robustly supported by empirical evidence and have fostered new research into the origins of inequality. Even critics acknowledge the value of asking big questions and seeking generalizable causes in world history.

7. Reception and Influence

Since its publication, “Guns, Germs, and Steel” has been integrated into curricula worldwide, from anthropology and world history to political science. It won the Pulitzer Prize and other prestigious awards, and inspired a PBS documentary. Its impact stretches into public discourse, helping to shift conversations about global inequality away from race and national character, toward environment, geography, and historical contingency.

Academics and general readers alike cite Diamond’s work as paradigm-shifting, its wide-ranging argument a model for synthesizing different forms of knowledge. It remains a touchstone in any serious discussion of human societies’ origins and trajectories.

8. Conclusion

Guns, Germs, and Steel endures as a landmark in scientific and historical literature. Jared Diamond’s meticulously argued book rejects centuries of lazy and harmful thinking about the fates of peoples and offers a material, ecological, and essentially hopeful account of our shared past. The forces that created the modern world were impersonal and rooted in deep history, not destiny or virtue. Diamond challenges us to see the development of societies through the lens of long-term environmental and geographic processes, and—by grasping these dynamic forces—encourages us to build a more just and rational global order.

In sum, the book’s lasting message is clear: history is not the story of the triumph of one race or culture over others, but of the complex interplay between environment, opportunity, and cumulative choices. By understanding these factors, we better comprehend both the tragedies and the achievements of our species—and perhaps glimpse the patterns shaping our future.

2 Comments

“Guns, Germs, and Steel” by Jared Diamond is a thought-provoking exploration of how geography, environment, and resources shaped civilizations’ fates. Diamond blends history, anthropology, and science to challenge racial and cultural explanations for global inequality, offering a compelling, fact-rich narrative that reshapes our understanding of human progress and societal development.

While Diamond’s geographic determinism offers a compelling macro-history, critics argue it oversimplifies cultural agency and historical contingencies. His Eurocentric framing downplays non-agrarian societies’ innovations. The environmental thesis is groundbreaking but risks ecological reductionism. Still, its interdisciplinary ambition makes it essential if debated reading on inequality’s roots.